Enclosed by 3.5km of citadel walls at the very heart of Beijing, the Unesco-listed Forbidden City is China’s largest and best-preserved collection of ancient buildings – large enough to comfortably absorb the 16 million visitors it receives each year. Steeped in stultifying ritual, this otherworldly palace was the reclusive home to two dynasties of imperial rule, sharing 900-plus buildings with a retinue of eunuchs, servants and concubines, until the Republic overthrew the last Qing emperor in 1911.

The year 2020 marks the 600th anniversary of the Forbidden City, which the palace intends to celebrate by ensuring more of the complex is open for visitors than at any other time in its history as a tourist attraction. Which is a longer history than you might think – the Palace Museum (故宫博物馆, Gùgōng Bówùguǎn), as the Forbidden City is officially called, first opened in 1925, just one year after Puyi, the abdicated 'last emperor', was evicted from the Inner Court.

Built between 1406 and 1420 by the Ming emperor Yongle, the construction of the Forbidden City was a titanic undertaking, employing battalions of labourers and craftspeople. Pillars of precious nanmu wood were floated from the jungles of southwest China to the capital, while blocks of quarried stone were hauled to the palace in winter over ingenious ice roads. Once built, the Forbidden City was governed by a stultifying code of rules, protocol and superstition; 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties governed China from its closed-off world, often erratically and haphazardly, until revolution swept them all away just a century ago. Despite its age, most of the buildings you see are post-18th-century Qing dynasty constructions and renovations – fire was a constant hazard, hence the enormous brass water vats everywhere.

Planning Your Visit

Although you can explore the Forbidden City in a few hours, a full day will keep you occupied and the enthusiast will make several trips. Most visitors focus their energies on the showpiece ceremonial halls and parade grounds, which take up the central axis in the outer court (southern half) of the complex. But the real thrill comes from exploring the labyrinth of courtyards and halls, laid out on a more human scale, on either side of the central axis, and from parading along the tops of the 10m-high walls for aerial views of the palace.

Entering the Forbidden City

In imperial times the penalty for uninvited admission was severe, although mere mortals wouldn't have even got close; the Imperial City girdled the Forbidden City with yet another set of huge walls cut through with four heavily guarded gates – including the Gate of Heavenly Peace, upon which hangs Mao's portrait. These days, tourists enter through the Meridian Gate, a massive U-shaped portal at the south end of the complex, once reserved for the emperor alone. Gongs and bells would sound imperial comings and goings, while lesser mortals used lesser gates: the military used the west gate, civilians the east gate and servants the north gate. The emperor also reviewed his armies from the Meridian Gate, passed judgement on prisoners, announced the new year’s calendar and oversaw the flogging of troublesome ministers.

Through the Meridian Gate, you pass into a vast courtyard and cross the Golden Stream (金水, Jīn Shuǐ) – shaped to resemble a Tartar bow and spanned by five marble bridges – on your way to the magnificent Gate of Supreme Harmony, beyond which the courtyard could hold an imperial audience of 100,000 people.

Mounting the Wall

Since 2018, visitors can climb the Forbidden City's Wall just inside and to the east of the Meridian Gate, follow it eastwards to the Corner Tower, and then north to the East Prosperity Gate. This route includes the Gallery of Historic Architecture, with exhibition spaces in the Corner Tower and the splendid East Prosperity Gate. In total, around three quarters of the 3.4km wall wall can now be climbed, a fine way to leave the crowds behind and take awesome photographs.

First Side Galleries

Before you pass through the Gate of Supreme Harmony to reach the Forbidden City’s star attractions, veer off to the west of the huge courtyard to visit the Hall of Martial Valour, where emperors would receive ministers. It houses a changing line-up of exhibitions. Just to the south is the Furniture Gallery, occupying an area known as the Southern Storehouses, which opened for the first time in 2018.

The Hall of Literary Brilliance complex to the east of the Meridian Gate was formerly used as a residence by the crown prince. It was rebuilt in 1683 after being destroyed by fire. It too hosts a changing line-up of exhibitions throughout the year, but is sometimes closed between November and March.

Three Great Halls

Raised on a three-tier marble terrace representing the Chinese character for king (王; 飞á苍驳), are the Three Great Halls (三大殿; Sān Dàdiàn), the glorious heart of the Forbidden City. The Hall of Supreme Harmony is the most important and largest structure in the Forbidden City, and was once the tallest building in the capital. It was used for state occasions, such as the emperor’s birthday, coronations and the nomination of military leaders. Inside the Hall of Supreme Harmony is a richly decorated Dragon Throne (龙椅; Lóngyǐ), from which the emperor would preside over trembling officials. The entire court had to touch the floor nine times with their foreheads (the custom known as kowtowing) in the emperor’s presence. At the back of the throne is a carved Xumishan, the Buddhist paradise, signifying the throne’s supremacy. Today you can only view it from the outside, and it virtually requires a rugby scrum to do so.

Behind the Hall of Supreme Harmony is the Hall of Central Harmony, which was used as the emperor’s transit lounge. Here he would make last-minute preparations, rehearse speeches and receive ministers. On display are two Qing dynasty sedan chairs, the emperor’s mode of transport around the Forbidden City. The last of the Qing emperors, Puyi, used a bicycle and altered some features of the palace grounds to make it easier to get around.

The third of the Great Halls is the Hall of Preserving Harmony, used for banquets and later for imperial examinations. The hall has no support pillars, and to its rear is a 250-tonne marble imperial carriageway carved with dragons and clouds; it was hauled into the city on an ingenious path of ice – they had to wait until winter to do so. The peripheral buildings surrounding the Three Great Halls were used for storing gold, silver, silks, carpets and other treasures, and now house museum exhibits.

Lesser Central Halls

The basic configuration of the Three Great Halls is echoed by the next group of buildings, reached through the Gate of Heavenly Purity. Traditionally, this gate was the dividing line between the ceremonial outer court and the inner court to the north, where the emperors and their entourages actually lived and worked. Smaller in scale, these buildings were more important in terms of real power, which in China traditionally lies at the back door.

The first structure is the Palace of Heavenly Purity, a residence of Ming and early Qing emperors, and later an audience hall for receiving foreign envoys and high officials.

Immediately behind it is the Hall of Union, which contains a clepsydra – a water clock made in 1745 with five bronze vessels and a calibrated scale. You'll also find a mechanical clock built in 1797 and a collection of imperial jade seals on display. The Palace of Earthly Tranquillity was the imperial couple’s bridal chamber and the centre of operations for the palace harem.

Imperial Garden

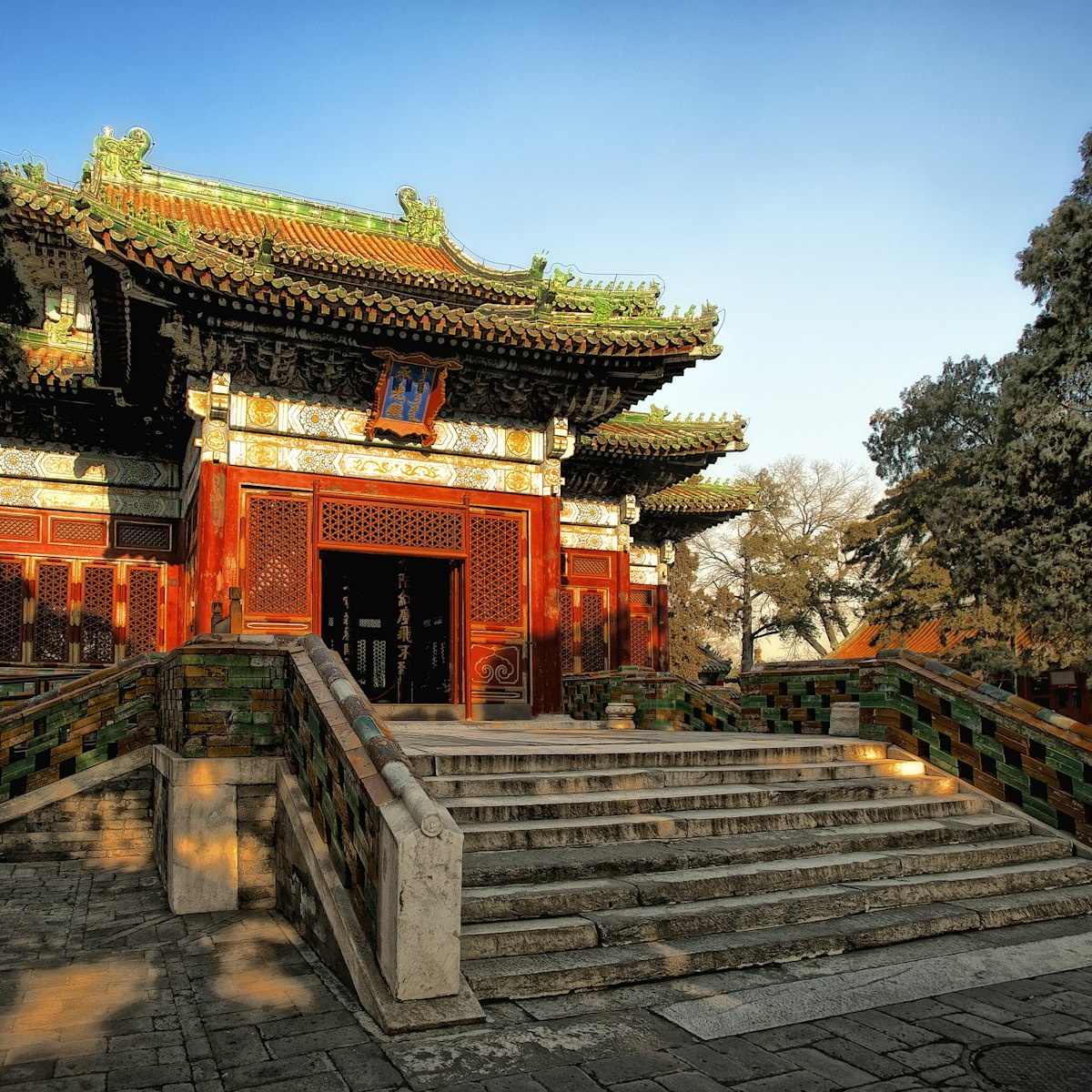

At the northern end of the Forbidden City is the Imperial Garden, a classical Chinese garden with 7000 sq metres of fine landscaping, including rockeries, walkways, pavilions and ancient, carbuncular cypresses. At its centre is the double-eaved Hall of Imperial Peace. Nearby, the Lodge of Spiritual Cultivation is where British tutor Sir Reginald Johnston gave English lessons to the abdicated 'last emperor' Puyi.

Treasure Gallery

On the northeastern edge of the complex is what feels like a mini Forbidden City all of its own. This is the Palace of Tranquil Longevity (宁寿宫; Níng Shòu Gōng), built around 1771 for Qing emperor Qianlong's retirement, though he never moved in. Today it holds the Treasure Gallery, one of the palace's most important collections of ornamental objects, which are crafted from gold, silver, jade, emeralds, pearls, and other gems and semi-precious stones.

The complex is entered from the south – not far from the unmissable Gallery of Clocks. Just inside the entrance, you’ll find a beautiful glazed Nine Dragon Screen, modelled after the one in Beihai Park.

From there you work your way north, exploring various halls and courtyards before exiting at the northern end of the Forbidden City. En route, seek out the Pavilion of Cheerful Melodies, a three-storey wooden opera house, which was the palace’s largest theatre. Note the trap doors that allowed actors to make dramatic stage entrances.

Western & Eastern Palaces

A dozen smaller palace courtyards lie to the west and east of the three lesser central halls. It was in these self-contained abodes, like far grander versions of Beijing's 蝉ì丑é测耻à苍 mansions in the hutong, where most of the emperors and empresses actually lived. Many of the buildings, particularly those to the west, are decked out in imperial furniture.

Other Attractions

Parts of the palace that were previously off limits are opening all the time. Due west of the Gate of Heavenly Purity are a collection of halls and gardens where the empresses and concubines of deceased emperors resided. Known as the Palace of Compassion and Tranquillity, it was used for storage for many decades after 1925 and today houses the Sculpture Gallery, which includes Buddhist statues, terracotta warriors, exquisite stone reliefs and more, from as far back as the Warring States period.

To the south is the Garden of Compassion and Tranquillity, where empress dowagers and imperial consorts worshipped the Buddha, entertained themselves and rested. To the west is the Palace of Longevity and Health, built for emperor Qianlong's mother.